Shareholders in South County Landmark Still Believe Their Stocks Will Pay Big Dividends

By Edward L. Carter

UtahValley360.com

Climbing yet another rickety wooden staircase inside the abandoned ore-processing mill east of Salem, I cannot shake the feeling that the Dream Mine is actually a nightmare.

Like many Utah Valley residents who have seen the multi-tiered, stark white structure in the south Utah Valley foothills, I have long desired to explore this curious relic of the 1930s. Unlike most Utah Valley residents, however, I experienced for myself the allure of “Bishop” John H. Koyle’s Dream Mine, also called the Bishop’s Mine or Relief Mine.

Although usually kept quiet, belief in the mine remains strong. Some people still have stock certificates squirreled away — just in case — and a crowd turns up in Spanish Fork each May for the annual shareholders’ meeting.

But just a few minutes into this rare tour, the allure of the mine has given way – for me, at least – to a cloud of depression. Maybe it’s the decades of dust and rust. Or perhaps it’s the thought of the men whose lives wasted away inside the cold, cramped shaft of one man’s dream.

The Dream Begins

The legend of the Dream Mine began in August 1894 with John Koyle’s nocturnal notion that he had been visited by Moroni, an ancient American prophet whose history is related in the Book of Mormon. Koyle later told others he had envisioned deposits of gold and treasure hidden inside a nearby mountain by the Nephites, a Book of Mormon group.

“This mine would be richer than anything like it in the whole world,” wrote author Norman C. Pierce in 1958, “but the big, rich deposits of ore [John] had seen would not be released to them until a time of great world crisis when all the people would be sorely in need of relief.”

Within a month of his first vision, Koyle had abandoned farming on his property south of Spanish Fork and had staked his first claims at the Dream Mine. He and five friends began digging in round-the-clock shifts. As the work progressed, Koyle claimed to receive direction for the mining operations through dreams and visions. Several years later, he was named bishop, or leader, of the Leland congregation of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

In 1909 the Koyle Mining Company was incorporated to sell stock in the mine. Funds were needed as operations expanded but no wealth was produced. The company sold stock almost exclusively to Latter-day Saints on the promise that the mine would someday save the church from financial trouble.

Then, in 1911, Koyle had a dream of the “Relief Bank.” According to accounts by those who knew Koyle, he stated that the Relief Bank would come forward with money and food in a time of financial collapse in the United States to save the stockholders of the mine and other members of the LDS Church.

But in 1913 church authorities warned members not to invest in any mine connected with dreams and visions. In December 1913 James E. Talmage, an apostle and geologist, inspected the mine and reported to LDS Church headquarters that there was nothing to it. Shortly after, mine operations were shut down, and the mine remained closed for more than six years.

Dreams Past & Present

Almost exactly 110 years after Koyle first began digging a vertical mine shaft into what locals call Knob Hill, I peer into a 2,300-foot long horizontal tunnel bored by “Dreamers,” as Koyle’s followers are sometimes called, to meet up with the original vertical shaft.

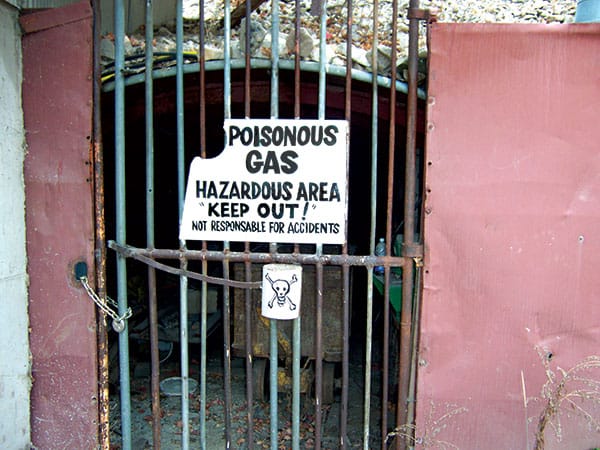

A locked gate prevents me from entering, and the Relief Mine Company, the entity that now owns the mine and about 1,800 acres of adjacent hillside property, has posted ominous signs warning of poisonous gases and other dangers.

I listen to stories told by L. DeLynn “Doc” Hansen, an Orem chiropractor and longtime mine believer. Hansen, an affable and knowledgeable tour guide, has graciously facilitated my visit to the mine and accompanied me there. He frequently refers to statements made by “the bishop,” or Koyle, and uses present tense verbs as if Koyle were still alive.

“It’s high enough on the mountain to be dry when the flood comes,” Hansen says of the mine portal. “The bishop says anything above the canal will be out of the water.”

Listening to Hansen, I surmise that owning stock in the mine is like joining an exclusive and secretive club. Stock that sold for $1.50 per share in Koyle’s day trades hands for about $8 per share today. True believers count on their stock becoming worth more than $1,000 per share when and if the mine becomes full of valuables.

Hansen calculates the major economic collapse will take place in October 2007, and he theorizes that the mine will begin paying its first dividends in December of that year. Soon after, believers say, people will flock to the mine area and construct a large community in the foothills east of Salem to be known as “White City.”

Hansen recounts his own conversion, as it were, to the mine. After graduating from chiropractor school, he set up his practice in Orem. Having become familiar with the mine as a youngster, he sought out the then-president of the mine, Quayle Dixon, who invited Hansen and his wife to the mine office at the base of the hill.

“I don’t know why but I took $300 with me, shoving it into my pocket,” Hansen wrote in a recent account. “My wife didn’t know anything about the mine, but she listened with me as Quayle told us the story of Bishop Koyle and his mine.

“Afterwards, he told us that the bishop recommended that a family have 100 shares of stock. I asked him how much a share was and he told me $3 per share. I pulled the $300 out of my pocket, and we became stockholders in the mine that day.”

It's Been No Fun

At approximately the time the mine was shut down in 1914, Koyle was released as bishop and moved his family to Idaho, where he resumed farming. But in 1920, after another vision, Koyle got the mining bug again and moved back to the Spanish Fork area. Reportedly, he had the blessing of LDS Church authorities to resume work at the Dream Mine as long as he did not claim to have had divine revelations.

But Koyle continued to claim divine revelations, and followers pointed to correct predictions such as the crash of the stock market in 1929, a local drought and the result of a presidential election. In 1932 he dreamed of a revolutionary ore-processing mill that would change the way metals were processed and would result in fewer lost profits.

Construction began on the mill, which is the structure still visible today at the base of Knob Hill. There were reports that ore with a value as high as $1 million per ton would soon be produced and that shareholders would get $1 per share every third day, with the remaining profits going to the LDS Church.

It didn’t happen.

Both federal and state securities regulators investigated the claims for evidence of fraud, but no legal action was taken against the mine company or its officers.

In 1939, mine stockholders built a house for Koyle and his family at the base of the hill on which the mine is located. In that house, which remains occupied and stands near another house that today serves as the mine company office, Koyle began to hold “Thursday night meetings” that combined religion, stock sales and encouragement for supporters of the mine who had yet to receive any benefit. Koyle reportedly became estranged from the LDS Church in 1948 and died in 1949.

In their respective writings about the mine, both Pierce and Hansen have recorded the heartbreak and trouble suffered by Koyle’s family.

“I have wished many times, and so have the children, that John had never had a dream about the mountain and the ore,” Koyle’s wife, Emily, wrote. “For years now, we have had people coming to our home at all hours, to learn all about the latest details. Some believe while others ridicule. It’s been no fun, I can tell you.”

Giving Up

Standing near the top of the mill that has never processed significant amounts of ore, I look down on Utah Valley below. It’s late October, and snow already has buried the upper mountains and threatens lower elevations.

A melancholy sadness has enveloped me, and I am not alone. Even long-time Dreamers who worked on the mine alongside Koyle himself have said recently there is a certain darkness about the site now.

Nothing I have seen has convinced me that the Dream Mine is any closer now to rendering nine rooms of Nephite gold bars than it was on the day Koyle first pushed a shovel into the earth here. Fabulous wealth and a glorious financial rescue seem unlikely results of the decrepit machinery, broken windows and drab rock I have seen.

I can’t say whether Koyle’s dream will come true, but, like Hansen, I don’t doubt Koyle believed it would.

“When you’ve been in the mine and seen that solid rock, you think nobody would do this unless they believed it was true,” Hansen says.