By Eric S. Peterson

Salt Lake City Weekly

Shareholders in the oldest mine to never make a real profit await word from an Angel to bring in the goods—but some are sick of waiting

Imagine, if you will, the the restless dreams of a turn-of-the century dirt farmer just trying to survive a hardscrabble life in the Utah territory circa 1894. It’s still two years before statehood, and this desert Zion remains a place of refuge to Mormon settlers — the self-titled Latter-Day Saints. To the rest of the nation, it’s still a bizarre quasi-theocracy, regarded with widespread suspicion even after its spiritual leaders barred the practice of plural marriage in 1890.

In this Rocky Mountain frontier, a very American religion is only just beginning to gain acceptance from the federal government and the world around it, which only decades prior had chased the Saints across the country, tarred and feathered and later murdered church founder Joseph Smith, and and at one point nearly gone to war with the settlers in the tense years prior to the American Civil War.

This community of devout pioneers had already carved a niche in the tapestry of the wild and wacky West, when a farmer in Spanish Fork, Utah, roughly 60 miles south of Salt Lake City, had a very strange dream.

On Aug. 27, 1894, John Hyrum Koyle dreamed he was visited by an angel who took him by the hand and, like the ghost of Christmas past, transported the awestruck Koyle from his bedchambers to a nearby mountain. The two passed through the dirt and rock of the hillside like fog, and in the heart of this mountain, the angel revealed to Koyle rich veins of gold and platinum, and nine vaulted chambers filled with treasures from the Nephites, an extinct race of people from the Book of Mormon.

The angel’s message was simple: these riches will help your people and will bring them relief in the lead-up to the end of the world.

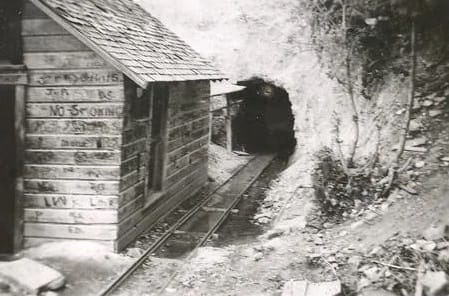

For the rest of his life, Koyle worked the “Dream Mine.” He brought a steady throng of followers out to join in him preparing the mine and built a mill on the hillside of the “Dream Mine,” later known as the “Relief Mine” by followers.

While the followers toiled and dug in a mine that never produced an ounce of paydirt or a dividend to shareholders, they did so with the faith that it was important work meant to ready them for the end.

Not all shared their faith, including the leaders of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, who by the mid-1900s had worked hard to gain acceptance into the mainstream fold of American life. They also didn’t appreciate a simple farmer having revelations for the entire church, and, in 1948, Koyle was excommunicated. His Dream Mine followers and shareholders went underground. But the dream never died.

To this day, there are still shareholders waiting for the signs prophesied in Koyle’s dreams. Signs, they believe, that will give them the green light to start pulling the riches from the mine that will allow them to build a bastion in the heart of Utah against a world that will crumble and implode around them.

I grew up in a small town about a five-minute drive from the mine, and through my father inherited some of this stock, which he had inherited from his father. My father wasn’t a believer in Koyle or the church; He was more of a country-fried hippie then your typical small-town Utah Mormon. He regarded the stock as a bizarre heirloom of the culture he was born into and rebelled against.

For the first large story I ever wrote as a reporter for a Utah alt-weekly, I examined this mine and followed the diehard faithful who have found safe haven in an e-mail discussion group, where they could talk freely and with anonymity about the mine as they prepared for the end days when it would be time to start digging.

My story about the dream in the digital age came out in late 2007. At the time, my editor regarded it as a nice slice of Utah’s very quirky history, and that was that. But shortly after the publication of that story, something unusual happened—the world ended.

By 2009, the housing bubble had popped spectacularly. Pensions wiped out, savings gone, and mortgages underwater. Perhaps most alarming for Koyle’s followers were the government bailouts of major banks and financial institutions, which called to mind Koyle’s cryptic prophecy that the economy would be “put up on stilts.” Koyle had even had some ominous dreams about the threat of Russia. During his time, some might have viewed those dreams as a reaction to the spread of communism in the first half of the 20th century and the beginning of the Cold War. But now, with Russia advancing on Ukraine and seizing land in Crimea, Dream Miners see more red flags. Indeed, Koyle at one time claimed that Russia would invade Turkey for access to the Black Sea.

These signs and others have lately energized a small revolt among Dream Mine believers and shareholders, led by a kindly former chiropractor named Delynn “Doc” Hansen. After the recession, Hansen gave up the chiropractic game to join several business partners in starting the American Relief Mint, which he says will be ready to begin minting currency from the ore of the Dream Mine once it comes in.

Hansen is also the creator of the e-mail group, and while the current board of the mine has taken a strong position against action until word is heard from “messengers”—possibly angels or a trio of “Nephites” who will come to give the signal— Hansen says the end has already begun and the time is nigh to get to work.

“I tell people if Bishop Koyle was alive today, would he be sitting around on his butt saying ‘Lets wait for the messengers,’ or would he be working trying to get the mine to come in?” Hansen says.

It’s a point that Hansen tried to bring to shareholders of the mine at their annual stockholder’s meeting, held May 12. But members of the board called the cops on Hansen and his followers, accusing them of trying to hijack the meeting. It was merely the most recent twist in a strange story of a mine that for over a century has inspired faith in a dream and the vigilant lookout for guardian angels who will likely take the form of the immortal remnants of a lost tribe of a people long since vanished from the Earth.

All that and more doomsday paranoia than you can shake a stick at.

Dead Ahead

Like Plato or Lao Tzu, Koyle was a visionary who didn’t bother to write down his dreams and teachings himself. It’s been said that he was instructed by God not to document his visions, leaving his followers to chronicle his various prophecies. While Koyle’s vision of the end times and the revealing of the mine were his most famous prophecies, they weren’t his first.

The first dream came after Koyle prayed fervently about a very personal matter—the location of a missing cow. According to the late historian Ogden Kraut’s book John H. Koyle’s Relief Mine, Koyle received an answer to his prayers in a dream where he saw his missing heifer in a field near a railroad track with a broken horn. When Koyle awoke, he visited the field and found his cow there, broken horn and all.

This dream was the first of many that would instill in Koyle a larger mission for the sake of the church. Apocryphal as these dreams are, according to those who knew Koyle, his dreams would, in startling succession, predict the 1929 stock-market crash, the commencement of two world wars, and of course, the mine’s very important role in providing relief to the Saints in the moments before the doomsday clock would run out on the world.

Before Koyle was a man of dreams, he was simply another man of faith like others in the early Mormon settlement. Koyle was devout, followed the word of the prophet without question, and lived a simple existence. It wasn’t an easy life on the frontier, however. Koyle became the head of his household when he was 9 after a quarry accident buried his father alive.

Koyle lived during hard years and held to his faith to get him and his family through. But once he started having dreams, he set himself on a collision course with the very church in which he’d had remained a lifelong member.

The LDS faith is unique as an American religion for many reasons even apart from the church’s early practice of polygamy, or The Book of Mormon, the thrust of which is that when Jesus was resurrected, he visited America to spread his teachings.

One of the most distinctive features of the religion is that its members have the ability to receive direct revelation from God. In LDS nomenclature, as long as members are devout to their faith, they will be able to hear the “still, small voice” of God. But there’s a catch: these revelations are only to guide the member about what they are to do about their own lives or that of their immediate family members. Only the church’s prophet receives revelation that affects the entire church.

Koyle’s Dream Mine revelation cast a much wider net than is allowed for a simple member of the church. But it was also one supported by many in his community. Koyle drew as many as 20,000 supporters of his vision during the heyday of the mine. In 1909, the mine was incorporated, and 114,000 shares of stock were issued for $1.50 each, with the assurance that when the Nephites’ treasure was unearthed, the value of the stocks would increase by more than tenfold.

The Dream Miners more than once bucked higher authorities—both religious and secular. In 1914, the church shut the mine down, though it was allowed to reopen six years later under the condition that it would be run as a business and not some kind of religious settlement. Koyle was said to have foreseen this turn of events in a dream and was unfazed by the temporary shutdown. The mine was also sued by the state securities commission for the sale of unregistered stock, but the case folded when it went to trial in 1933 and witnesses for the prosecution instead spoke up to defend Koyle and his divine mission.

During the first half of the 20th century Koyle seemed bulletproof because of the zeal he commanded among his shareholders. The bottom line of this support wasn’t about dividends; it was about faith, faith that led thousands to buy stock or offer their labor on the mine in exchange for it. They call Warren Buffet a wizard, but Koyle’s Dream Mine boasted tens of thousands of supporters, an army of volunteer laborers and somehow, in 1932, during some of the worst years of the Great Depression, Koyle even had managed to raise $60,000 in capital—more than $1 million in 2014 dollars, when adjusted for inflation—to build an ore-processing mill on the hillside.

Koyle was even said to have started a small settlement around the mine dubbed “White City” where mine workers would live and Koyle would deliver regular sermons. Eventually, his following provoked a direct rebuke from the higher-ups in the church. Apostle James. E. Faust, who was also a geologist, called Koyle out as a charlatan in a 1928 issue of The Spanish Fork Press, labeling Koyle’s work as that of the “evil one.”

Koyle made a target of himself, not just through his work in the mine but by openly challenging the authority of church leaders. According to Norman Pierce’s The Dream Mine Story, Koyle believed that when the mine came in it would offer a reality check to all doubters, including in the church, saying that at that time “… in rapid sequence, the church, state and nation will be brought up a standin’ to judgment like a wild colt to a snubbin’ post.”

At the age of 84, Koyle was called in before a church council and made to sign a statement repudiating his visions. He immediately regretted the move, and in defiance, he continued his work on the mine for another year until he was excommunicated from the church in 1948. Rejected and shunned by the leaders of his faith as a con man, Koyle died less than a year later.

In the subsequent years, many of his followers went underground. Many more, fearful of losing their membership in the church, burned their stock or hid it away in attics and basements, not to be spoken of … until, of course, the time was right.

Apocalypse Now

When I first spoke to “Doc” Hansen in 2007, the mercurial, middle-aged chiropractor and organizer of the Dream Mine e-mail group owned up to his own morbid fascination with the end of the world the way someone with a chuckle admits to love watching The Bachelor. There was a bit of a hobbyist’s fascination in the way Hansen looked out for the warning signs. In 2007, he referenced an account from a Dream Mine follower that Koyle had said the beginning of the end would be marked by a great financial crash, followed by people waking up the next day to find no power, light or heat in their homes.

At the time of our conversation the economy was still roaring and Hansen’s prediction for the end was simple: electromagnetic pulse. Hansen figured someone could deploy such a beam, perhaps in Russia, to knock out all major electronics in the country and send the United States back into the stone age, thus fulfilling Koyle’s prophecy about a loss of power.

When I met Hansen recently in the food court of a mall in Orem, a college town 30 minutes north of the mine, his theory about the end of the world was a lot closer to the reality Americans have been living with for the past five years—economic collapse. Hansen says it will come after the Federal Reserve raids banks to collect on trillions in outstanding loans.

“How much money do you want stolen by the government? Because that’s how much you should leave in the bank,” Hansen says. “I leave just enough in the bank to pay the bills and the rest I keep in silver and gold.”

Though Hansen’s views of the end times have changed over the course of the most recent recession, like other shareholders, he says his relationship with the mine has been guided directly by the helpful hand of the spirit. Hansen says it was a spiritual prompting that led him to create the e-mail discussion group on Sept. 10, 2001, the eve of another calamity. Hansen’s seen the group grow since then from a handful of friends to more than 1,200 members.

Since the latest recession gut-punched the economy, Hansen has now found his role in the Dream Mine as that of a gadfly, an agitator asking the Dream Mine board to consider the possibility that the signs they’re waiting for to bring the mine in have perhaps already come in—indeed, that the signs might have occurred during Koyle’s lifetime.

Hansen refers to several prophecies that happened while Koyle was alive, such as the prediction of the Great Depression, or his famed “Republican Elephant Dream” in which Koyle predicted an unprecedented series of Democratic victories that would cause the Republican elephant to sink to its knees. A dream many have attributed to the repeated elections of Franklin Dealano Roosevelt to a historic 12 years in office.

Hansen says that regardless of the prophecies, building up and rebuilding the existing mine infrastructure should be the focus of the shareholders, and while Koyle was alive, he never stopped working to unearth a profit.

“The project is over a hundred years old, it was meant to bring people relief—it hasn’t brought anybody relief,” Hansen says. “You know what it takes? Someone getting off their duff and saying, ‘I don’t have fear to get this thing going.’”

Hansen became more vocal among shareholders and on the discussion group about the need to start digging. He gave up chiropractics and joined several business partners in creating a mint. When he was first approached by the men who would become his partners, he says, they asked him if he knew of anyone who would like to invest in the company.

Hansen told them he would think of some names, but “all of a sudden, the spirit says, ‘No, you’re the person that’s supposed to do this and if you do it, this is the mint that’s going to mint the stuff up at the Dream Mine,’” Hansen says.

Up and running since, 2013 the mint acquired two old presses from the San Francisco Mint and now has the technology to push out 100,000 coins a week.

Hansen says if the riches of the mine are to provide relief, that’s something that needs to happen while there’s still a functioning economy. If the world’s on fire and overrun with zombies then no amount of gold or silver will be of much use.

The mint also provided Hansen with another reason for why his fellow shareholders should demand the mine be developed and renovated now. Given all the repairs and new technology that needs to be put into the mine, Hansen says, it will be impossible to get the equipment if the board waits until the economy is in shatters.

“We put [the mint] together during a good economy, and it took us over a year to find the equipment and get it here and to find people to get it up and running,” Hansen says. “Over a year in a good economy. Good luck in a bad economy.”

Still, Hansen says, it’s unlikely they’ll be able to vote out the existing board of the Dream Mine and replace it with members more amenable to starting to dig. In order for that to happen, 51 percent of shares would have to be registered. Hansen says shareholders will have to continue to deal with board members who have been extremely cautious with the mine and refuse to dig until they get the word from on high.

Hansen has clashed openly with the board. Last April he and his business partners requested permission to visit the mine property and assess the existing mill and other structures only to be threatened by the board with arrest for trespass. A week later a sheriff’s deputy visited him at the mint, responding to complaints filed by the board, that he trespassed on the mine.

Hansen was also involved in a strange clash with the former president of the board who sent him an e-mail saying he had a dream in which Hansen’s deceased father had spoken to the president and told him to pass a message to Hansen that he needed to start focusing on church more than the mine.

“He sends me this thing that’s supposed to be from my dad—and there was nothing familiar about it,” Hansen says. In the message, he says his father’s alleged spirit called Hansen by his first name “Delynn” when he says in real life his father always addressed him by the nickname “Dee.”

Hansen promptly took this proof of the president “channeling familiar spirits” to the board. The board president later stepped down from the leadership spot and moved to Colorado.

Although the chances of enough shareholders turning up to vote out the board, are slim, Hansen has a few other tricks up his sleeve for seeing the mine come in. At the time of our meeting, he was planning to hold a meeting directly following the stockholder’s meeting to talk about what’s needed on the hill and how to make it happen. Despite the antagonism, Hansen tells me he knows the board personally and considers most of them friends; he just wishes they could understand the threat.

“They’ve convinced themselves we shouldn’t do anything until we’re told what to do. You see the storm coming and you do nothing—the watchmen on the hill,” Hansen says with a scoff. “Its like, ‘Hey look at that great big storm coming—pass me more lemonade.”

Before our meeting was over, I asked Hansen about his 2007 prediction of a storm cloud on the horizon, the possibility of Russia pulling the trigger on an electromagnetic pulse that would wipe out power across the country.

“Oh, there’s still talk of that,” Hansen says matter-of-factly. “North Korea even has that capability. It’s perfectly possible.”

Angels in the Auditorium

On May 12, more than 100 Dream Mine shareholders and curiosity seekers gathered at the Veteran’s Memorial Building just off Main Street in Spanish Fork, Utah. The shareholders packed into an auditorium, filling aluminum folding chairs that faced a simple stage with an American flag standing in a bucket. Outside the entrance, a man set up a tent to sell DVDs about a gamut of conspiracy theories—the end of the world, New World Order references made by Dick Cheney at a Brigham Young University commencement speech, the so-called truth about the Sandy Hook shooting, and others.

“I got lots of flavors of ice cream here,” the kindly man said waving his hand across the crowded table of DVDs, just $2 a copy.

Inside there was a healthy buzz as the crowd found seats and looked around at their fellow shareholders. As I sat down I wondered how many others in attendance were watching to see if one of the messengers or angels would make his way into the meeting and find a seat.

It’s a legitimate thought among Dream Miners, given that Koyle at one time was said to have been visited by two of the three Nephites. In the Book of Mormon, the Nephites were a race of people that connected Israel with the Americas. Lehi, an Israelite prophet, had his son Nephi rescue the golden plates—from which the Book of Mormon would eventually be translated—and the family left Jerusalem for the Americas.

Generations later, according to the Book of Mormon, Jesus rewarded the loyal service of three Nephite disciples by granting them immortality, telling the trio that they “would never taste death.”

For many in the LDS faith, the three Nephites are akin to wandering angels. Koyle was said to have been visited by two of the Nephites, one tall and thin the other short and stout who told him that when the mine was in trouble, they would be there to help.

Hansen recalls being told a story of a Dream Mine follower who swore to having met one of the Nephites at a Checker Auto Parts in Spanish Fork in the 1970s. The man, a Checker employee spotted a man with a large beard who appeared to be “dressed behind the times.” When the Nephite made his way to the front, he asked the man if he would show him how to fix the fender of his car. Hansen says his friend showed the strange man how he could mend the bumper with a few simple parts and some elbow grease. After the man finished his advice, the Nephite said: “Son, thy sins be forgiven thee” and then got in his car and drove off.

At the shareholder meeting, I spotted more than one elderly man sporting a beard worthy of a biblical prophet, but they all seemed to be pretty chummy with the other shareholders and weren’t dressed any more “behind the times” than anyone else in attendance. Given the high percentage of older shareholders, pretty much everyone was dressed “behind the times” in simple work clothes—jeans, boots, BYU ball caps, Western shirts and suspenders.

The meeting began with a simple prayer and the Pledge of Allegiance. Seated on the stage were a handful of stern-faced board members who seemed to be bracing themselves for a potentially quarrelsome meeting.

Larry Hadfield, a member who had joined the board to lend his accounting experience, approached the podium sporting a baby-blue Western shirt and a bald-eagle belt buckle to read out the financial report.

The mine itself has never produced a significant profit from any of its digging, so shareholders have only been able pay the bill on the mine thanks to a few tangential revenue streams: a small number of rental properties on the hill, a fruit orchard and a lease on an adjacent gravel pit. As Hadfield explained some of the numbers on the prior year’s profit and loss sheet he stopped to ask for questions. A man in his late 30s stood up and got right to the point, even if it wasn’t the kind of question the board was asking for.

“Why don’t we start mining?” the man said. “We’re not here to manage rental units! When are we going to start mining?”

The response drew rowdy applause from probably a third of the shareholders in attendance and a single, prolonged “Boo!” from one man.

Boyd Warren, a board member bearing an uncanny resemblance to Teddy Roosevelt with his short cropped hair and mop-handle mustache, took the mic to counter the man’s question.

“Can I ask you a question?” Warren said. “Have you received information from anyone that now is the time?” Again, applause echoed the board member’s call for restraint but somewhere in the back I can hear Hansen call out, “Bishop Koyle worked on the mine until the day he died!”

After a while the babble and groans died down and the meeting pressed on.

Ray Koyle, the mine secretary took the podium to read the stockholder’s report and deliver the news that Hansen and his fellow mine mutineers knew was coming: with 77 percent of the company’s stockholders confirmed at a valid address, only 31 percent had registered their stocks to be represented at the meeting—a number well short of the 51 percent needed to vote in new board leadership.

One woman rose to ask why it was fair for active shareholders to be held back by those who couldn’t care less about registering their stock and attending the meeting.

Koyle—a descendant of the Bishop Koyle—explained calmly that free agency was respected by the mine and just because a shareholder doesn’t now want to participate in the mine doesn’t mean they won’t ever want to get involved, especially if they believe later on that the time is ripe to bring the mine in.

“There’s no one on this earth that has the right to say, ‘Oh you haven’t done this for 10 years— then we’re going to cut the legs out from under you,’” Koyle said.

Koyle then called on a man who arose from the crowd wearing a straw cowboy hat and a dirt-stained white shirt stretched over a watermelon gut. The man’s face was tanned from plenty of work outdoors and he smiled broadly as he introduced himself as a “messenger.”

“I’m one of the messengers you’re looking for. I’m here because the Lord asked me to be here, to my shock. I am the Metal Man,” the man said by way of introduction. (Later in the parking lot I spotted the man’s truck for a scrap metal-pick up business showing his picture under the slogan “Its like maid service on steroids!”)

“I pick up stuff for free all over Utah Valley,” said the Metal Man. “I’ve given over six tons of rebar to friends of mine at no cost, over 30,000 cinder blocks to friends of mine at no cost, I’ve given a years’ worth of food supply to over 10 families at no cost to me. If you’ll put me on the board, I can help expand the roads, provide rebar. I can get concrete donated—I can do a lot of things and I know a lot of people that do a lot of things.”

Koyle deftly told the man to give his information to the mine secretary for consideration, thank you very much, and kept the meeting moving along.

Following a few outbursts and the offer from a would-be messenger, the meeting ended without further incident. The real drama occurred when Hansen and his mine mutineers attempted to hold their unofficial meeting in the same building after the conclusion of the shareholder’s meeting. Hansen says they had received express permission from the building owner to have their meeting, but the board members immediately challenged Hansen, saying they had reserved the building for the entire day.

As Hansen and his cohorts took the stage, board member Warren immediately got on his cell phone and called the police. While two-thirds of those who had come for the official meeting had stuck around for the second meeting, the sight of a verbal skirmish between the board members and Hansen’s group caused most of them to get up and skedaddle. I tried to get a contact number from Warren, who told me that if I wanted to learn about the mine, then I should read the two books about it. As for getting the mine ready now, Warren said he wasn’t interested in do-it-yourself mining.

“If we start mining now, what’s going to happen when OSHA comes in and shuts us down?” Warren asked.

And if it were done up to code?

“Then do you got $5 million bucks? Because that’s what its going to take. But even then every nickel and dime of royalties will get reported to the state,” Warren says.

Hansen’s group held the high ground on the stage for a while, but didn’t want to get arrested and eventually ceded the stage to hold a meeting in the parking lot. On their way out I picked up a snippet of Hansen’s conversation complaining to the board secretary, who told Hansen: “Well you shouldn’t be saying such nasty things in your e-mail group, Doc…”

By the time the meeting spilled into the parking lot, only a dozen folks were there to hear the message. Hansen had brought out one of his mint partners, Steve Wardle, a man with mining experience who had assessed the infrastructure at the mine to talk about what could be done.

It wasn’t an ideal meeting. In a small circle at the end of the parking lot, Wardle, a short silver-haired man, spoke to a crowd while a cold wind whipped around them and an ominous thundercloud appeared to be dumping its guts over the mountains to the north of town, threatening to do the same over the parking lot insurrection. Adding to this scene was the presence of the police. This being a small rural community in Utah County on a Monday afternoon it appeared the police didn’t have anything else pressing going on and therefore responded to the trespass complaint with two police trucks, a patrol vehicle and an undercover vehicle, all hovering around the meeting as Wardle spoke. The officers never interrupted but simply watched with bemused grins. Eventually they deemed the crowd unlikely to riot and dispersed.

Wardle had a sermon to share and it started with grim news. He told the crowd that the mine was terribly out of date. The wiring in the mill was shot, the wood was rotten in the mine itself, and a pipe system was undermining the ground underneath a water tank and would likely cause it to come rolling off the mountain one day. For that matter, the mine and mill were built adjacent to the Wasatch fault, and with one good shake, the mill itself would come tumbling down.

The upshot of this grim diagnosis was that the mine needs revamping and it needs it soon, which means the mine needs believers who will fix it now. And just as the mine needs relief now, so too do people deserve to have the riches inside the dilapidated mine.

“The idea of waiting for an [economic] crunch or a collapse is ludicrous, it’s nuts,” Wardle told the small crowd. “Besides, it says that God wants you to suffer before he’ll help you. God wants you to be poor, destitute, struck down—everything wrong in your whole world, and then maybe you’re worthy of help. Or maybe God says I love you, I will take care of you, I bless you and I will never forsake you—so get your butt in gear.”

The crowd was in complete agreement, but several asked how they could do anything about the mine without ousting the current board and what would happen if they were to start digging?

“The police will come and kick you off the mountain,” Wardle said. “Unless Jesus has a plan —and he does, I’m aware of that plan, I know what it is in my heart but its just what he told me. And I’m a nobody. Why have I done this all these years—because I’m totally insane!” Wardle bellowed to a smattering of chuckles from the crowd. “There is no other reason! But the first thing we must do is come together with a common desire. This doesn’t have to take two, three of five years. It requires coming together once and establishing the desire and never letting it go away.”

But making an end-run around the board might take more than just a loving gathering—according to Wardle the mine’s charter expired in 1958 and the board simply rolled the old corporation into a new one without first putting it to a vote of the shareholders.

“We got attorneys in Salt Lake City looking into the problems of rolling one corporation into a new one,” Hansen told me at our mall meeting. “They find enough problems there you could literally break the current corporation.”

The Beginning of the End

For more than a century, the Dream Mine has existed because the image of it burned so brightly in the vision of one man that he wouldn’t be satisfied until he made it a reality. Koyle worked his mine for over 50 years only to die penniless, having never seen a significant profit pulled from the mine. After his death active mining ceased as the church issued repeated proclamations against the mine that drove former Koyle acolytes underground for fear of losing their church membership.

Perhaps in the end Koyle was grateful, knowing that if the mine didn’t produce that meant the world was going to keep on turning.

But what would Koyle make of the fracas currently dividing the board of his beloved mine? Would it bring a tear to the eye of this farmer turned prophet? Would he see the legacy of his work wasted on a new generation hellbent on heavenly riches? Or is it possible that nothing really surprises a man who can see into the future.

If you believe in any of Koyle’s visions or at least accept that the predictions, as reported by followers, do seem to synch up with history, then it’s hard not to at least wonder about the prophecies that have yet come to pass.

Author Ogden Kraut’s Relief Mine II: Through Other’s Eyes catalogs various news articles, dissertations and firsthand accounts of followers discussing the mine. One section of the book collects an appendix of 102 prophecies Koyle was said to have made to his followers. There are prophecies of what will happen before the mine comes, like “there will be a harsh winter followed by a mild open winter.” There are also apocalyptic prophecies about what will happen during the end, such as “the mine will become a city of refuge against roving bands” and that “the leaders of the nation will be blown out of office as if by a whirlwind.”

Prophecy number 15 states: “Toward the end a group will try to bring the mine in early but will not succeed. It is best not to attempt to bring the mine in early because if it is done the government will tax it away, or take it over for its important strategic values.”

Hansen is dismissive of this prophecy. He believes the mine was meant to come in during Koyle’s lifetime and thus doesn’t consider bringing the mine in now to be “early” and certainly doesn’t see anything wrong with at least updating the mine infrastructure now so that its ready.

Another prophecy from the book states: “The mine will not come in until 11 families can live in perfect unity and harmony.” Hansen doubts those words came from Koyle and believes them to be a reference to the United Order.

The United Order is a strange chapter in Utah’s history. Early Mormon settlers, under the guidance of Joseph Smith and Brigham Young, attempted to live in essentially socialistic communes, sharing the fruits of their labor in common with their fellow citizens. In many ways, Koyle’s vision aligns with this idea. For Koyle the mine was a divine work, not just a means for Koyle and his partners to strike it rich and blow their money on loose women and the dopest horseless carriages money could buy. Instead, Koyle planned to use the money to help his fellow man and build up the kingdom of God.

Renowned historian of Mormon history and culture D. Michael Quinn says Utah had a very distinct break with the collectivist vision of its early church leaders right around the time that Koyle had his first vision in the 1894. It was a time when the LDS Church was working to be accepted into statehood and was similarly embracing outside commercial interests that brought industry, jobs and money into the state.

“In the 1890s there was a clear abandonment of polygamy and clear abandonment of the [principles of the United Order] and a clear embrace of commercialism and free enterprise” by the post Brigham Young leadership of the time, Quinn says.

Nowadays, Mormons in Utah are overwhelmingly conservative, pro-business and look back on the socialistic ideas of Smith and Young as “dusty memories,” Quinn says. He adds that in many ways, these are ideas that are revered in the present day but have also been abandoned.

It seems clear that few of the current Dream Mine supporters feel that the surest way to bring in the mine would be to try living the principles of the United Order. It’s a little too Occupy Wall Street for most folks in the heart of the most conservative county in one of the most conservative states in the nation.

But the idea of coming together is not something that’s been totally abandoned by the Dream Mine faithful.

At the close of the official shareholders meeting, before the cops were called, Board President Leroy Rose took the podium to close out the meeting and offer some earnest words of wisdom. Rose, a great grand son of Koyle, recalled the sage advice of a choir teacher who emphasized the need to “blend”— to harmonize with the different voices in the choir to make something larger and prettier than the voice of any one alto, bass, or tenor.

“If we do not blend we’re not successful,” Rose said. “So if I can do one thing I would say the Lord recognizes when we work together.”

Eric S. Peterson is a reporter for the Salt Lake City Weekly. His investigative interests include white-collar crime, poverty issues, government ethics, activist groups, religious fraud, and alternative cultural takes on The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In his spare time he reads, fishes and practices kung fu. Follow him on Twitter: @EricSPeterson